Sunday Morning Post, September 29, 1991

Mao fever spreads across nation as memories begin to fade

By PAUL MOONEY in Beijing

Anyone who has walked down the streets of Guangzhou or Shenzhen recently cannot have missed the plethora of Mao Zedong paraphernalia on sale and adorning the windshields of taxis, buses and lorries.

Just 15 years after his death, the Great Helmsman is enjoying a new surge in popularity as Chinese with short memories dust off their Mao badges and posters and the propaganda machine churns out a steady stream of material celebrating his memory.

But while “Mao fever”, as the Chinese press calls it, seems to have infected all corners of the country, the underlying reasons appear less than uniform.

The phenomenon first surfaced during the pro-democracy movement in 1989, when students and intellectuals began wearing Mao badges as a tacit form of protest against Mr. Deng Xiaoping and the rest of the leadership. It has since taken on new and varied forms.

In July, an estimated 2,000 people swam the Yangtze River in memory of the 25th anniversary of Mao’s famous swim, and in August more than 3,000 students from Yunnan province took off on a trip to retrace Mao’s 9,600 kilometre Long March of the 1930s.

Young people have taken to sporting T-shirts emblazoned with a smiling Mao and one of his famous sayings, and one man in Sichuan province has set up an unofficial Mao museum in his home, proudly burying himself under more than 18,000 Mao badges and other paraphernalia.

Young people have taken to sporting T-shirts emblazoned with a smiling Mao and one of his famous sayings, and one man in Sichuan province has set up an unofficial Mao museum in his home, proudly burying himself under more than 18,000 Mao badges and other paraphernalia.

Mao, who spent much of his life trying to eliminate “feudal superstitions” and cutting off “capitalist tails”, would turn over in his grave if he knew he had been elevated to the status of shen or god, endowed with the power to not only repel evil, but also promote capitalism.

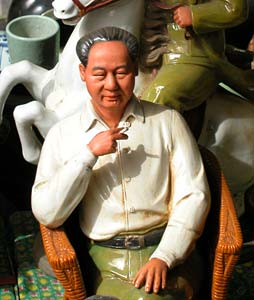

Some rural families have put small statues of Mao on their family altars, where they burn incense and make offerings.

On the streets of the capitalist-leaning Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, laminated Mao photos are a hot item at newspaper stands.

The photographs are stuck on the windshields of buses, lorries and taxis.

“I put the photograph of Mao on my window to ward off evil,” a young Shenzhen taxi driver said, adding he greatly admires Mao.

And entrepreneurs, the capitalist tails that Mao so badly wanted to cut off, are putting up large portraits of Mao, ruthlessly employing the image of the staunchly anti-capitalist to pull in more business.

One shopkeeper in Guangzhou, who said things had been slow recently, claimed business took a sharp turn for the better after he put a Mao portrait on the wall.

According to one story going around China, Mao’s saintly abilities can be traced back to the summer of 1989, when protesters threw a bucket of paint on the huge Mao portrait hanging over the entrance to Beijing’s Forbidden City.

The portrait was covered with a cloth until a new one could be put up, and, as the story goes, Beijing was hit by an eerie torrential rain, apparent evidence of Mao’s heavenly dissatisfaction.

The strongest push for a revival of Maoism has come form China’s elderly hardliners, who have raised Mao’s ghost to counter the sharp drop in the party’s prestige, as well as their own loss of credibility, in the wake of the 1989 crackdown.

Since 1988, more than 50 books by and about Mao have been published, with several million copies reportedly sold, including Mao Zedong Military Theories. The second edition of The Works of Mao (Vol. 1-4) came off the presses on July 1 for nation-wide distribution.

The People’s Liberation Daily has exhorted soldiers to “deeply study Mao Zedong’s military theories”, and the Guangming Daily has claimed Mao’s aberrations were actually the result of “distortions” of Mao thought.

A kinder and gentler Mao is also being portrayed.

Mao and His Son, a film released last summer, examines Mao’s relationship with son Mao Anying, showing Mao Zedong close to tears after learning of his son’s death in the Korean War.

Mao’s teenage years have been made the topic of two recent dramatisations for young people, and Mao’s poems have been set to music and recorded.

And now, as the country prepares to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Mao’s birth in 1993, his birthplace is enjoying an economic boom that has pushed annual incomes past the national average.

According to the New China News Agency. Mao’s fellow villagers have set up 26 restaurants and 151 stands and shops in the hope of cashing in on the one million visitors expected to make the pilgrimage to their village.

Nor has Hongkong managed to escape Mao fever. One foreign resident hiking on a far corner of Lantau recently stumbled across a Mao “temple” where a small group of villagers had obviously just been worshipping Mao. Inside the small structure was a makeshift altar with a portrait of Mao surrounded by several small statues of the late leader, and even a small Red Guard doll.

Of course, not all Chinese have forgotten the Mao-inspired economic and political foibles that plunged the country into chaos so many times. Nor does everyone look upon the Mao era as a golden age of clean and efficient government.

One Chinese friend, who argues that life today is much better than during the Mao period, sums up Mao fever in one word: “Neo-ignorance.”